The opera “ Madame Butterfly ” was written by the Italian composer Puccini in 1904, based on the short story written by John Luther Long in 1898. It begins with a scene in which a Japanese marriage-broker, Goro, shows Pinkerton, a Lieutenant in the US Navy, a Japanese traditional house. Pinkerton is surprised to see that the walls in the house are slidable to suit his lifestyle. The newlywed Pinkerton asks where is the bedroom, Goro answers by sliding the walls. “Here or there! Wherever you wish!”

Every time I see this opera, I am amazed to rediscover that the Japanese flexibility of living arrangements was already famous in Europe at the end of the 19th century – soon after the remarkable 250 years of isolation under the Tokugawa shoguns ended in 1868, and Japan opened diplomatic relations to the West.

The Japanese walls are called “Shōji” and “Fusuma”. In my opinion, Shōji and Fusuma represent perfectly the Japanese mentality. Shōji and Fusuma are panels made out of paper with wooden frames, placed on wooden rails so that they can slide. Thus, they are walls and doors at the same time. You can just slide whichever panels you like to use as a door. They are also easily removable and can be stored in a designated area in order to make far larger spaces within. Flexible, practical, rich with possibilities, and ambiguous, you may say.

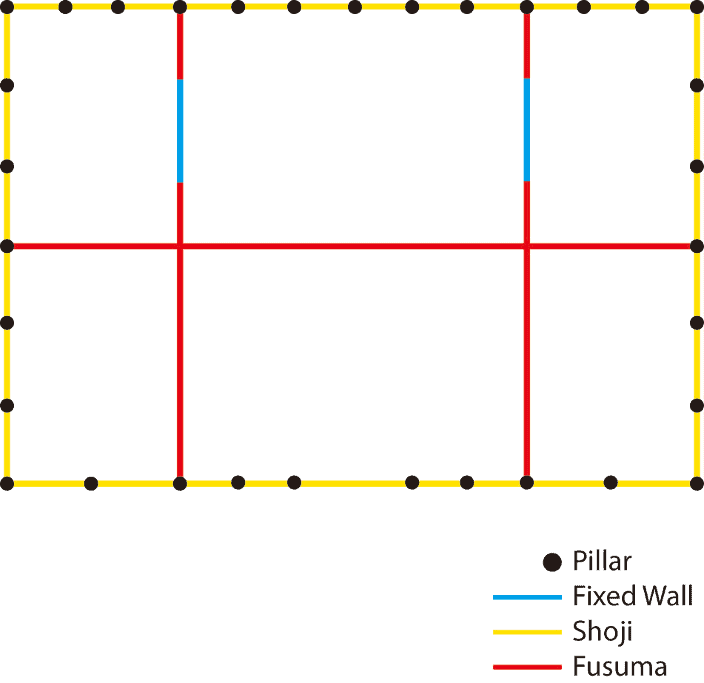

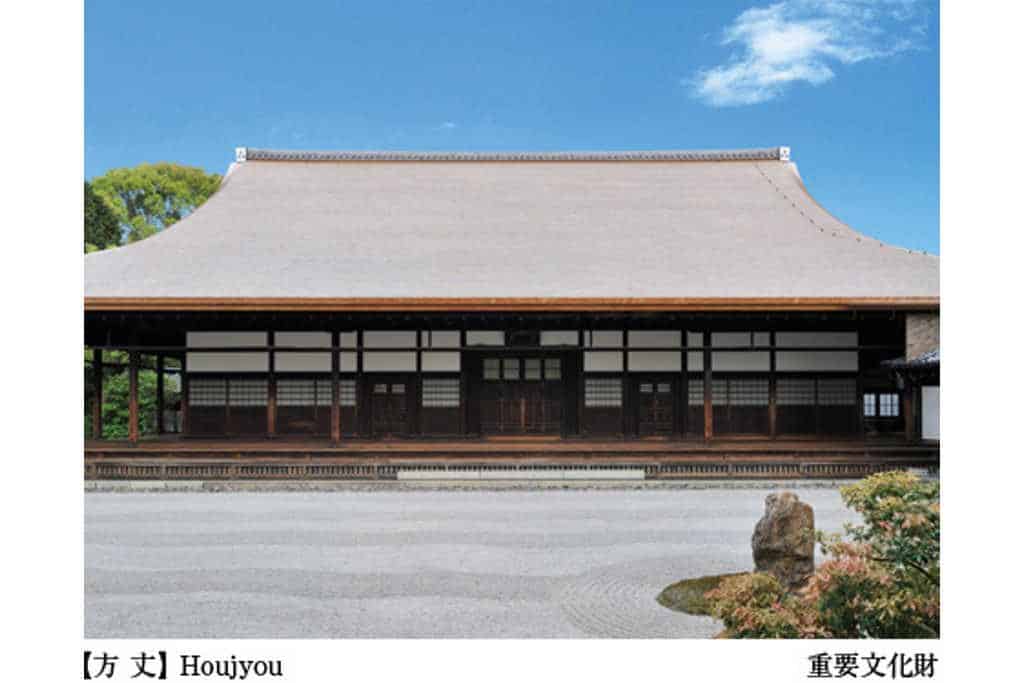

Let’s take a look at Kenninji. Kenninji is the main temple of Ryosokuin, the temple where I held my New Year’s exhibition in 2013. It’s known as the oldest Zen temple in Kyoto, Japan. The floor plan of the Houjou, the main hall of Kenninji, was built around the 14th or 15th century and moved in 1599 to where it now stands. You will see that Kenninji has roughly 50m Fusuma and 70m Shoji in total, and only 6m 29cm of fixed walls. Thus, only 5% of all of the walls are fixed.

Here are some examples of what Kenninji Fusuma look like. You can see that these walls are perfect examples of both Japanese perfectionism and fine art.

(See more examples of Kenninji Fusuma)

In western culture, walls are traditionally built with stones. Stone walls symbolize one’s diligence, maturity and carefulness, and the inflexibility of stone walls is highly praised. But in Japan, this is not the case. Something which is thought to be the symbol of inflexibility, such as a wall, is also changeable, depending upon your feeling, making the atmosphere in a building totally different. This shows how important flexibility is for Japanese.

Being flexible to adjust meant, in Japan, to be diligent, mature and careful. This concept of being flexible in Japanese traditional architecture – to adjust the space so that it suits one’s lifestyle, occasion, and season – is called Shitsurai 室礼 (しつらい). The Japanese legacy of Shitsurai still exists everywhere in Japanese culture, for example, in ikebana and the tea ceremony. Ikebana is a part of Shitsurai, adjusting rooms with flowers so that rooms match the season or occasion. Like Ikebana, Kana Shodo is also a part of Shitsurai. It reflects people’s desire to adjust rooms with the use of seasonal poems. Decorative papers are used in addition in order to create a matching atmosphere.

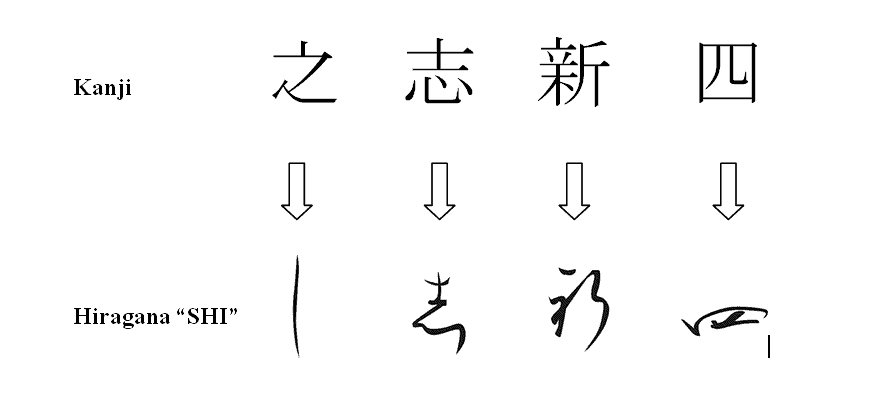

Flexibility also exists in aspects of Japanese traditional calligraphy, specifically in Kana-Shodo. Kana-Shodo uses Japanised Kanji and traditional ancient Hiragana characters in its writing. As I explained in my previous article, only 46 Hiragana are used in modern Japanese daily life, but until 1900 there were a couple of hundreds of Hiragana characters. Japanese hiragana characters were created based on Kanji characters imported from China, and there were many varieties of Hiragana with the same pronunciation based on different Kanjis. For example, here are some of the Kanjis transformed into hiragana characters all with the pronunciation “SHI”. Only the simplest form of SHI on the very left hand side is still used in modern daily life in Japan.

This is surprising considering the fact that in western culture “A” is always “A” and can never be written with any other character/letter. But in Kana Shodo, there are no concrete rules for choosing which Hiragana character to use to express the sound “SHI”. So you may choose whichever “SHI” you wish, depending merely on your chosen design and how you are feeling

|  |

| In places where you want to write narrow and long, you could choose the Hiragana shown above. | If you wish to write in more heavy and wide form, then you may choose the Hiragana shown above. |

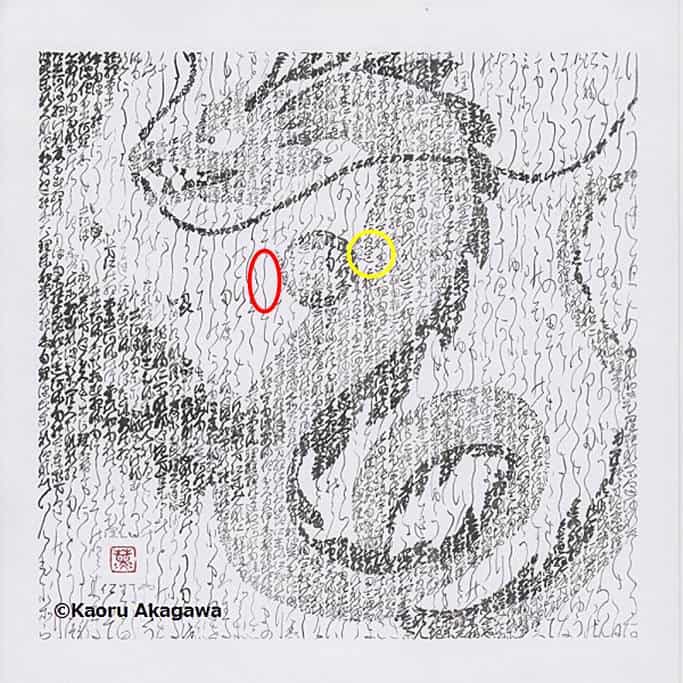

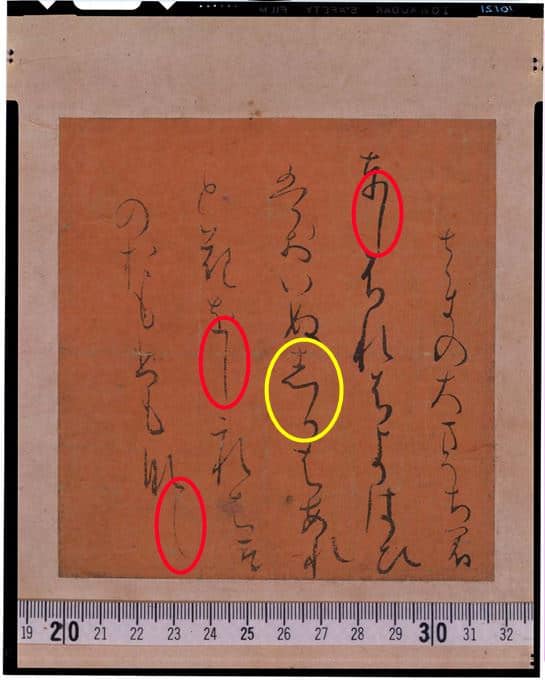

The following image is a part of one of the most famous masterpieces of Kana Shodo, Sunshoan Shikishi. The calligrapher used two different types of “SHI” in this work. Paying particular attention to the middle where you have two different types of “SHI” placed next to each other, it would have looked totally absurd if the calligrapher had used the same character side by side. Instead, the calligrapher has succeeded in making a great contrast using the diversity of Hiragana.

This is comparable to how easily Fusuma can change the floor plan and the atmosphere in a house. Just by changing the selection of the Hiragana character you use, you can change the atmosphere of your work.

Ironically, the rich possibilities of Hiragana made writing and reading Kana Shodo too complicated. It was the main reason the Japanese government decided in 1900 to reduce the number of hiragana in common use to 46. But this richness is also one of the reasons why Kana Shodo is so sophisticated and refined. Due to this cultivated fineness, Kana Shodo won the hearts of the highly educated aristocratic women in the Middle Ages.

In my art, Kana de l’Art, which I developed myself based on my technique as a master of Kana Shodo, I also use this diverseness of hiragana in order to create contrast. In places where I want to make the image to appear lighter, I choose the simplest form of hiragana. And in places where I wish to make the work darker, I use hiragana with more strokes so that it looks denser and darker. This enables me to create images without changing my brush or ink color. My art is possible because of the rich, flexible diversity of Kana Shodo, and I am grateful to my predecessors, the aristocratic women in the Middle Ages, for this beautiful Japanese writing culture. If only Puccini knew about this affluent Kana Shodo culture, his opera “ Madame Butterfly ” might have been five minutes longer to depict Pinkerton’s deeper surprise!