1.Meaning:

nine

2. Readings:

3. Etymology

九 belongs to the 象形文字 (しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji, i.e. set of characters of pictographic origin). It is a pictograph of a dragon, or more precisely a dragon-serpent (龍蛇, りゅうだ, ryūda, i.e. “a wingless dragon (with a bent body of a serpent and dragon head, often armed with branch-like horns)”). The ancient forms of 九, both the oracle bone and the seal script versions (as shown in Figures 1 and 2), depicted the bent figure of a dragon-serpent (according to some scholars, it was possibly a female dragon; such a conclusion was based on its curvy and supple shape).

The ancient shapes of all characters for numbers are based on ancient astrological and magical beliefs. They are closely related to the forces of the universe and the eternal balance that rules those forces. Those forces were eventually categorized into Yin and Yang. Yin (陰, いん, shadow) elements are associated with the female world, and Yang (陽, よう, sun) elements are associated with the male world.

According to what we read in 易経 (Chinese: Yì jīng, i.e. “The Book of Changes”), whose original text was written on bamboo slips around the mid-3rd century B.C., 九, being an odd number, represents the Yang side of the world. 九 is a sacred number, often applied in ancient Chinese myths and legends that involve the supernatural. They are known in Japanese as 祭祀歌謠 (さいしかよう, saishi kayō, i.e. “religious ballads”) composed for worshiping gods of nature.

The dragon was a creature appearing in Chinese myth and folklore since at least the 5th millennium B.C. Dragons, Yang creatures, with its Yin counterpart, the Phoenix, together they manifest the harmony of universe’s natural forces, and their ever-lasting tendency to balance one another.

It is not unusual that dragons were used by the emperors of China as symbols emphasising their power. One of them was the legendary emperor 禹 (Chinese: Yū, c.a. 2200 – 2100 B.C.). The character 禹 (used only for the name of this particular ruler) is a combination of 虫 (Chinese: chóng, i.e. “worm”, “insect”, though it is also a generic term for animals) and 九 (dragon).

The sound of the character 九 is not accidental either. Its onomatopoeic nature symbolises the sound of an item being bent; it is not a coincidence that words such as 觓 (きゅう, kyū, i.e. “to stretch (a bow string)”, or “to curve”), 捄 (きゅう, kyū, i.e. “to scoop (for example, a mound of earth), 樛 (きゅう, kyū, i.e. “to bend”), or 亀 (きゅう, kyū, i.e. “curved (for instance curved back, resembling a shape of a turtle’s shell)”, although the main meaning of 亀 is “turtle”), have identical sounds in Japanese, and identical or very similar sounds in Chinese, to the ones of the character 九.

4. Selected historical forms of 九.

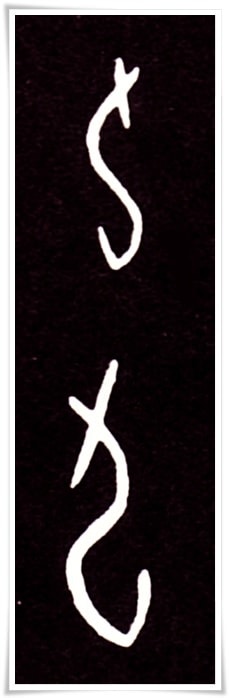

Figure 1. Oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) forms of 九 starting from ca.1600 B.C.

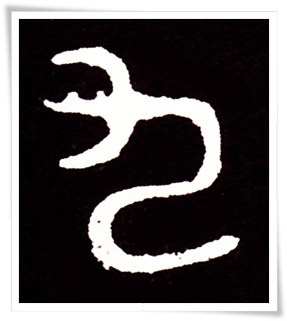

Figure 2. Ink rubbing of kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”)form of the character 九, found on one of the 盂鼎 (Chinese: Yú dǐng) bronze vessels, which was cast during the Western Zhou dynasty (西周, 1027 – 771 B.C.).

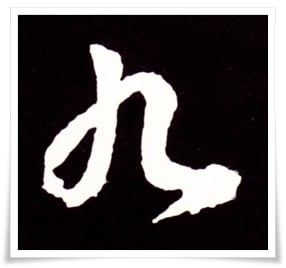

Figure 3. Clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 九, found on the stela 史晨碑 (Chinese: Shǐ chén bēi) erected during the reign of 漢靈帝 (Hàn Língdì, 156 – May 13, 189), the emperor of the later Han dynasty (後漢, 25 – 220 C.E.). If you compare this particular form of the clerical script with oracle bone script and kinbun forms, you will notice the connection between the modern shape of this character (Figure 5) and its ancient pictographic appearance.

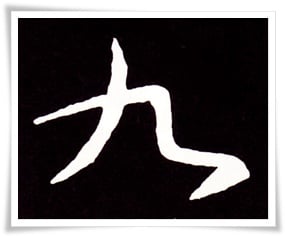

Figure 4. Ink rubbing of the cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 九 taken from the calligraphy work entitled 澄清堂帖 (Chinese: Chéng qīng táng tiē) attributed to 王羲之 (Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361), often referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖; Chinese: shū shèng), Jin Dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420 C.E.). The original work did not survive (in fact, none of the original works of 王羲之 exist), and the rubbing was taken from a stele erected during the Ming dynasty (明朝, 1368 – 1644 C.E.).

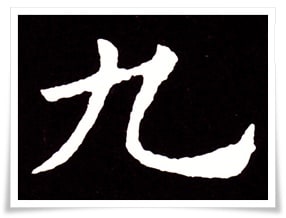

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of one of the variations of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) forms of the character 九, taken from the Jiucheng Palace stele (九成宫碑, Chinese: Jiǔ chéng gōng bēi), Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907 C.E.).

Figure 6. Semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) of the character 九. Ink rubbing from the stele 昇仙太子碑 (Chinese: Shēng xiān tài zǐ bēi), erected in 699 C.E., on the order of 武則天 (Chinese: Wǔ Zétiān, 624 – 705 C.E.), the only woman in the history of China that assumed the title of Empress Regent. 武則天 was also an outstanding calligrapher, and she is well known for her flying white style (飛白, かすり, kasuri). The text on 昇仙太子碑 was composed and written by her as well.