Gyousho (行書, also known as walking or running style) was the last of five major styles to appear. It was the natural result of everyday handwriting. Whenever a calligrapher decided to put his thoughts down slightly faster and in more emotional manner he inadvertently laid foundations for a semi-cursive script. Gyousho is understood as a bridge between more “rectangular” styles (kaisho 楷書, and reisho 隷書) and draft script (草書, sousho).

Similarly to kaisho and sousho, gyousho is based on stroke order, although not as strictly as the former, yet more rigidly than the latter. On rare occasions stroke order may differ from that in standard and cursive styles. The whole idea of running script is to allow for more fluent brush movements, merging certain lines, and creating a “softer” image of characters than in standard script.

A calligrapher can at times merge styles through writing in semi-cursive script, although it is much easier to do in cursive hand (sousho). To be able to do so one needs very strong knowledge of other styles.

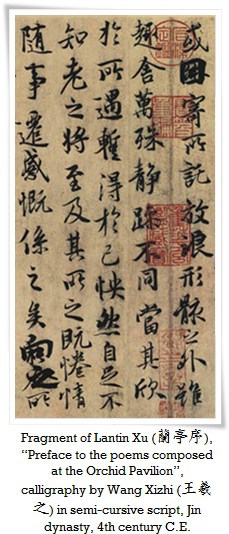

The legend says that gyousho was developed from reisho by a calligrapher and scholar of the late Han dynasty (後漢, 29 B.C. – 219 C.E.) Liu Desheng (劉德昇, c. 146-189), and was perfected during the Jin dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420) by the great father and son of the Wang family: Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303 – 361) and Wang Xianzhi (王獻之, 344 – 386), often referred to as “the Two Wangs”.

Of course, in reality none of the styles was a creation of one person. Nonetheless, each of them has its own grandmaster. In case of gyousho it was indisputably Wang Xizhi.

The most remarkable masterpiece in semi-cursive style ever created is Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion (蘭亭集序, Chinese: Lantingji Xu) by Wang Xizhi, written in 353 C.E. after few glasses of wine. It is not only a story of a drinking and poetry writing gathering of 42 artists, but possibly the most valued calligraphic treasure of all time. Lantingji Xu is also the source of many idioms and sayings commonly used today, as well as the subject of numerous theatrical plays and novels.

From artistic point of view, Wang Xizhi’s style was extremely rich and ahead of his time. Emperor Wu of Liang (梁武帝, 464 – 549), a founder of the Liang dynasty (梁朝, 502 – 557) once remarked of Xizhi’s sho, that “(it) is as powerful as dragon jumping through the Heavenly Gate, and a tiger crouching in the Phoenix Tower”.

After the night Xizhi wrote his masterpiece, he endeavoured to repeat his performance but even though he completed hundreds of copies he was never able to surpass the original.

To master gyousho, one needs to study kaisho with understanding and control. Standard script should be executed slowly and with focus on composition, characters shape, overall balance and stroke order. Walking style is a layer resting on the shoulders of this knowledge, assuming that the calligrapher has a strong foundation. As in life, first a child tries to sit, then it walks, and finally has the skill, balance and strength to attempt running.

There is no rigid boundary between cursive and semi cursive styles. In fact, some of the characters’ forms are impossible to classify. The interim script is called gyousousho (行草書, walking draft script) and if it is closer to kaisho, then we call it gyoukaisho (行楷書, walking standard script).

Gyousho offers the calligrapher a great freedom, allowing him to capture his soul’s true state at the time of composition in a powerful and less cumbersome manner, with rules of form slightly loosened, and the limits of balance stretched further than in kaisho. On the other hand it is much more readable than sousho making it very comfortable and pleasant for both writer and reader.