Background

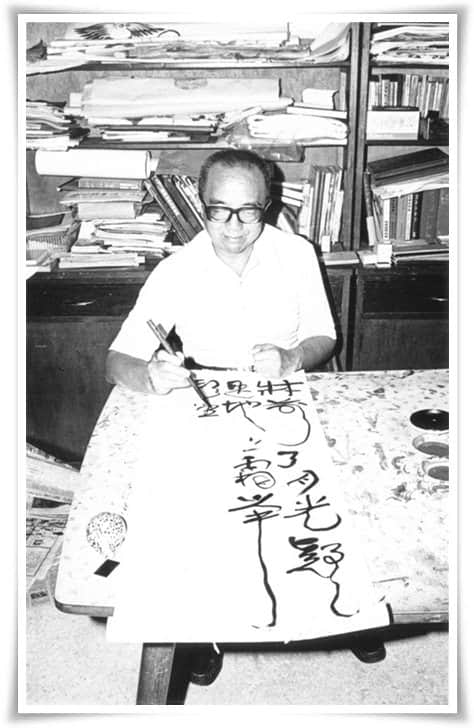

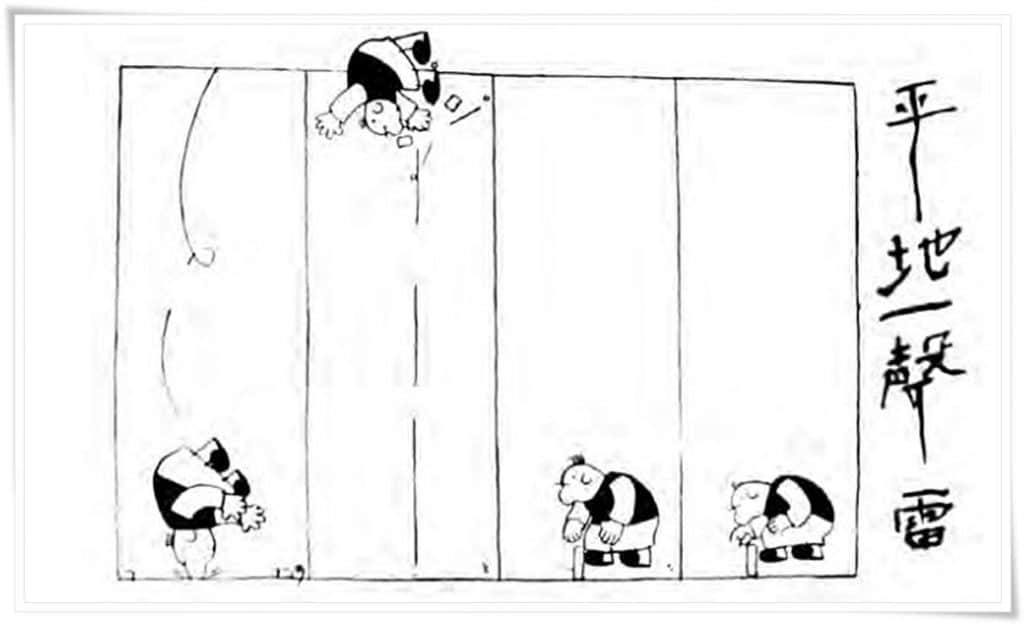

“The Dictionary of Chinese Art” published in Shanghai in 1989 and Taiwan in 2001 described Huang Yao (1917 – 1987) as a contemporary Chinese artist, famous for his cartoon characters (Niu Bizi) in China, as well as his book published in 1967 on “The History of Chinese in Malaysia and Singapore”1. Huang Yao had remarked that he was by profession a journalist, by accident a cartoonist, and he painted all his life.

Perhaps it was the exposure to complex issues in society as a journalist (and later as a cartoonist) together with his mastery in calligraphy and painting, that enabled Huang Yao to come up with ingenious solutions, the creation of Chuyun Shu to solve the problem he encountered in calligraphy in 1934 and in the late 1960s, the creation of Wenzi Hua or paintings of ancient Chinese characters as an innovative response to the loss of beauty and pictorial root in the simplified written Chinese.

With regard to Chinese calligraphy, Huang Yao wrote :

“Under a macroscopic viewpoint, it is none other than painting a picture with lines and dots,

and those characters that bear resemblance to tangible objects in real life are concrete,

while those that represent intangible things are abstract.”2

This may explain why Huang Yao was able to write upside down, as he was actually painting the Chinese characters. The writing of characters, for him, was just another way of painting lines and dots using the Chinese brush and black ink, with pictograms a concrete picture is formed as in the Wenzi Hua, while for all the other script, the painting is abstract or what is known as Chinese Calligraphy.

Chuyun Shu or Rising Cloud Writing

Huang Yao’s father taught his young six year old son calligraphy and painting, according to the tradition of literati families. He practiced on a smooth city-wall stone and used pure rainwater as ink for economic reasons. This was also an important training for the strength needed to write well.

By the time he was sixteen years old, he was a journalist with the largest newspaper in Shanghai (Xinwen Bao). He was skillful in calligraphy but found his writing “artificial”. Knowing that a writer’s personality is reflected in his calligraphy, Huang Yao was frustrated that his writing had no reflection of the “natural delight” of innocent child-likeness that he felt was very important in life.

He befriended many children and observed how they wrote. He found children’s writing to be more similar to drawing than writing and full of natural delight. However, try as he might, his writing could not attain the look he wanted as his proficiency in calligraphy stood in the way. In time, he stumbled upon a technique to achieve the effect he was looking for. It was by writing the Chinese characters upside down! The writing resembled those written by children and Huang Yao was thrilled. He used this technique to write all the inscriptions of his cartoons.

This naïve, childlike calligraphy was perfect to accompany his early drawings that exuded innocent humor. He was very famous in China for his cartoons from 1934 until 1947, when he left the country.

This unusual way of writing upside down attracted a great deal of attention and requests for demonstrations. He wrote and wrote happily, until he became so fluent and fast in his writing, that the words appeared to be rising from the bottom of the page like clouds ascending from the hills. Huang Yao named his writing Chuyun Shu (or rising cloud writing). It comes from a phrase from Tao Yuanming’s poem, “the cloud unintentionally rises from the mountain peak”. The movement of clouds is natural and not premeditated, which is also how Chuyun Shu should be executed, that is, spontaneously and without conscious effort.

At first glance, Huang Yao’s calligraphy appears to be similar to Chinese calligraphy executed in the traditional way. But upon close examination, following the order and direction of how the strokes of the characters should be written, the viewer would often able to realize that the Chinese characters were actually written upside down.

Stay tuned for part 2, where we will continue with some distinctive features of Huang Yao’s calligraphy

Another exmaple of Huang’s Yao work can been seen here

An interview regarding Huang Yao’s Chuyun Shu can be found at the link here.

For more examples of Huang Yao’s calligraphy, please refer to huangyao.org.

References:

1 Li Xianwen, “Zhongguo Meisu Cidian” (Dictionary of Chinese Art), Hsiung Shih Art Books Co.

Taiwan, Ltd., 2001. 1st edition by Shanghai Cishu Chubanshe, 1989.

2 Huang Yao, Shufa Rike or Daily Practice of Chinese Calligraphy, “Moyuan Suibi” (Jotting in

Relation to Ink), collected articles by Huang Yao, edited by Pan Qingsong, Kuala Lumpur:

Chinese Assembly Hall 2000, pp.122-125.