1. Meaning:

come out, exit, go out, leave, protrude, put out

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): い.だす, い.でる, だ.す, -だ.す, -で, で.る

- Onyomi (音読み): シュツ、 スイ

- Japanese names: いず, いづ, いで, じ, すっ, すつ, てん

- Chinese reading: chū

3. Etymology

出 belongs to the 象形文字 (しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji, i.e., set of characters of pictographic origin). It is a pictograph of a footprint, or more precisely an imprint of the heel with the addition of a curved line engulfing its lower part.

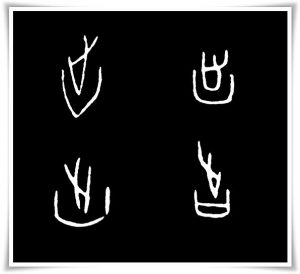

The shape of the character 出 symbolises a step forward executed with vigour; each step starts from placing the heel on the ground. A strongly placed foot would ruffle the sand around the heel which could explain the curved line below the heel (Figure 1). However, that is not the case.. You will notice that the shape of this curved line resembles that of a ritual vessel (called さい, sai; see the etymology of the character 口 {くち, kuchi, i.e. “mouth”} for more details) used for occult practices (Figure 1). This is not accidental. The curved line that imitates such a vessel symbolises a ritual performed by a traveller who seeks good fortune and protection from disaster. This ritual was performed prior to undertaking a journey.

A similar ritual is known to exist in ancient Japan. Known as uma no hanamuke (馬のはなむけ, うまの はなむけ), the literal translation is “in the direction towards which a horse’s nose points ”. Before departing, a prayer was said aloud for the sake of the safety of all travelers present in the given group.

In “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, pinyin: Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), we read: 進也。象艸木益滋,上出達也。(pinyin: Jìn yě. Xiàng cǎomù yìzī. Shǎng chū dá yě.), which can be interpreted as “(Character 出) is based on the concept of advancing, based on an image of rapidly growing grass”.

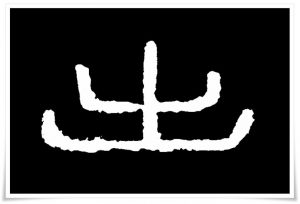

However, the bokubun (卜文, ぼくぶん, i.e. “divinitory texts of the Shang dynasty {商朝, pinyin: Shāng Cháo, 1600 B.C. – 1046 B.C.}”) and kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) texts clearly show a pictograph of a footprint, and there is no connection to vegetation whatsoever (Figures 1 and 2).

4. Selected historical forms of 出.

Figure 1. Various forms of the character 出 in oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun), Shang dynasty (商朝, pinyin: Shāng Cháo, 1600 B.C. – 1046 B.C.). Note the clearly visible vessel “sai”, used for religious rituals, in the lower part of the character in the bottom-right corner of the picture.

Figure 2. Ink rubbing of kinbun (金文) form of the character 出 from the three legged bronze vessel named Mao Gong Ding (毛公鼎, pinyin: Máo gōng dǐng), Western Zhou dynasty (西周, pinyin: Xī Zhōu, 1046 B.C. – 771 B.C.) , c.a. 9 century B.C.

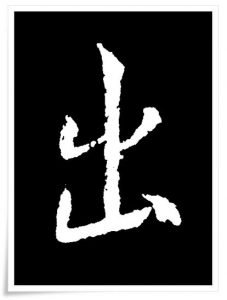

Figure 3. Clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 出. The ink rubbing comes from the stele “Stone Gate Eulogy for Yang Menweng” (楊孟文石門頌, pinyin: Yáng Mèngwén shímén sòng). The text is often used for the study of the clerical script of the late Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), 148 C.E.

Figure 4. Cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 出, found in the writing by an outstanding ink painter and eccentric calligrapher of the The Song Dynasty (宋朝; pinyin: Sòng Cháo, 960 – 1279 C.E.) Mi Fu (米黻, pinyin: Mǐ Fú, 1051–1107 C.E.), also known as Mi Fei (米芾, pinyin: Mǐ Fèi).

Figure 5. Standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) form of the character 出, from the Jiucheng Palace stele (九成宫碑, pinyin: Jiǔchénggōng bēi), text attributed to a brilliant Tang dynasty (唐朝, pinyin: Táng Cháo, 618 – 907 C.E.) calligrapher, Ouyang Xun (欧陽詢, pinyin: Ōuyáng Xún, 557 – 641 C.E.), 637 C.E.

Figure 6. Ink rubbing of semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) of the character 出 found in the calligraphy work compilation entitled 集王聖教序 (pinyin: Jíwáng shèngjiào xù), created by the order of the Emperor Taizong of Tang (唐太宗, pinyin: Táng Tàizōng) of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, pinyin: Táng Cháo, 618 – 907 C.E.). The characters for this work were chosen from the masterpieces of Wang Xizhi (王羲之, pinyin: Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361 C.E.), often referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖; pinyin: shūshèng) who lived during the Jin Dynasty (晉朝, pinyin: Jìn Cháo, 265 – 420 C.E.).

5. Useful phrases

- 出発 (しゅっぱつ, shuppatsu) – departure

- 出張 (しゅっちょう, shutchō) – business trip

- 輸出 (ゆしゅつ, yushutsu) – export

- 出口 (でぐち, deguchi) – exit

- 出席 (しゅっせき, shusseki) – attendance

Text: Ponte Ryūrui (品天龍涙)

English editing: Rona Conti

Japanese/Chinese editing: Yuki Anada