1. Meaning:

ten

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): と, とお

- Onyomi (音読み): ジッ, ジュウ, ジュッ

- Japanese names: い, か, ぎ, さ, し, そ, そう, ち, とう, ね, ま, る, わ

- Chinese reading: shí

3. Etymology

十 belongs to the 指事文字 (しじもじ, shijimoji, i.e. set of characters expressing simple abstract concepts). The original idea expressed by the oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) forms, as well as some of the kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) forms, suggest that the shape of 十 was based on the concept of a vertically oblong tool used for calculations (Figures 1 and 2). Please also refer to the etymology of the character 一 (いち, i.e. “one”).

According to the Shuowen Jiezi (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì, i.e. “Explaining Simple [Characters] and Analyzing Compound Characters”) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), Xu Shen (許慎, pinyin: Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), the character 十 was an object used for counting with numbers displayed on its surface.

The very same book also states that the character 十 symbolises the centre of the four directions of the world (i.e. East, West, North, and South). This theory seems to be often cited and used as an explanation of the etymology of 十. However, one must remember that Shuowen Jiezi was written over 1700 years before the discovery of oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun), thus the theories therein are not always correct. The divinatory (卜文, ぼくぶん, bokubun), and, surprisingly, kinbun (金文, きんぶん, lit. “text on metal”) forms of 十 are all single vertical lines, though some kinbun forms display a swelling towards the the centre of the stroke or a plump dot. None of the kinbun forms has a horizontal line crossing the vertical one. Consequently, the above theory by Xu Shen seems incorrect.

The vertical line that you can see in the modern form of the character 十 is an aesthetically altered fat dot which first appeared in the kinbun script. The same modern form of the character 十 was incorporated to form the characters of multiplications of the number 10. The number 20, for instance, is often written in calligraphy as 廿 (にじゅう, nijū, i.e. “twenty”), and not as 二十 (にじゅう, nijū, i.e. “twenty”).

4. Selected historical forms of 十.

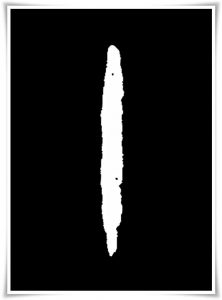

Figure 1. Oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) form of 十, Shang dynasty (商朝, pinyin: Shāng Cháo, 1600 B.C. – 1046 B.C.).

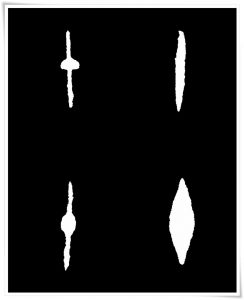

Figure 2. Various kinbun forms (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) of the character 十. The ink rubbings come from different types of vessels of the Zhou dynasty (周朝, pinyin: Zhōu Cháo, 1046 B.C. – 256 B.C.) period, from a memorial washbasin (弔上匜, pinyin: diào shǎng yí), top-left, to a bronze food dish (盂鼎, pinyin: yú d ǐ ng), bottom-right.

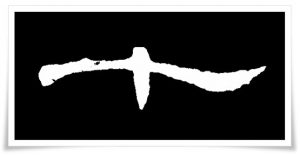

Figure 3. Ink rubbing of a beautifully balanced mature clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 十, found on the stele 曹全碑 (pinyin: Cáo quán bēi) from the late Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.) period, erected in 185 C.E. Mature clerical script is also known as happun rei (八分隷, はっぷんれい, lit. “eight parts clerical [script]).

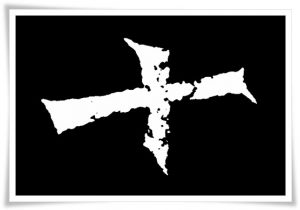

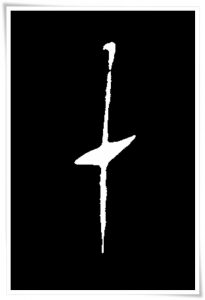

Figure 4. Ink rubbing of cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 十 found in the Autobiography (自敘帖, pinyin: Zìxù tiē) attributed to Huai Su (懷素, pinyin: Huái Sù (725 – 785 C.E.) of the Tang Dynasty (唐朝, pinyin: Táng Cháo, 618 – 907 C.E.).

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) form of the character 十, from a stele which name could be translated as follows: “Buddhist statue inscription for mourning deaths of Sun Quisheng, Liu Qizu, and others” (孫秋生劉起祖等造像記, pinyin: Sūn Qiūshēng Liú Qǐzǔ děng zàoxiàng jì), erected in 502 C.E. The text is written in the very powerful style characteristic of the Northern Wei dynasty (北魏, pinyin:Bĕi Wèi, 386 – 534 C.E.), and it is attributed to Xiao Xianqing (蕭顯慶, pinyin: Xiāo Xiǎnqìng, birth and death dates are unclear). This stele is one of twenty calligraphy masterpieces carved into the rock of the famous Longmen Grottoes (龍門洞窟, pinyin: Lóngmén d ò ngkū), a cave in Eastern China.

Figure 6. Light and agile semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) of the character 十 from one of the masterpieces by a Confucian scholar, brilliant calligrapher and a highly ranked official of the early Tang dynasty (唐朝, pinyin: Táng Cháo, 618 – 907 C.E.), Yu Shinan (虞世南, pinyin: Yú Shìnán, 558 – 638 C.E.).

5. Useful phrases

- 十月 (じゅうがつ, jūgatsu) – October

- 十歳 (じゅっさい, jussai) – ten years old

- 十時 (じゅうじ, jūji) – ten o’clock

- 十日 (とおか, tōka) – 10th day of the month

- 四十路 (よそじ, yosoji) – the age of fourty

Text: Ponte Ryūrui (品天龍涙)

English editing: Rona Conti

Japanese/Chinese editing: Yuki Anada