Japanese calligraphy is defined by two major styles. One of them is known as karayou shodou (唐様書道, からようしょどう, karayō shodō, lit. “Tang dynasty style calligraphy”), the other is wayou shodou (和様書道, わようしょどう, wayō shodō, i.e. “Japanese style calligraphy”). To read about both in greater detail, please refer to the History of Japanese Calligraphy section on our main page, here.

Japanese calligraphy was dominated by the Tang dynasty (唐朝, Chinese: Táng cháo, 618 – 907 C.E.) style for many years. Chinese masterpieces and their copies were flowing into Japan, and they shaped Japanese calligraphy. Nevertheless, the persistent search for aesthetics that would exemplify Japanese taste and tradition led to the development of what is referred to as wayou shodou. The pioneers of this style were the famous Sanpitsu (三筆, さんぴつ, i.e. “three brushes”) and the Sanseki (三蹟, さんせき, lit. “three traces”) of the Heian period (平安時代, へいあんじだい, 794 – 1185). The three Sanpitsu were: Emperor Saga (嵯峨天皇, さがてんのう, 786–842, the 52nd emperor of Japan), Tachibana no Hayanari (橘逸勢, たちばな の はやなり, 782 – 842, a governmental official), and Kuukai (空海, くうかい, Kūkai, 774 – 835), a Buddhist monk and scholar. The three Sanseki were: Ono no Michikaze, also known as Ono no Toufuu (小野道風, おの の みちかぜ・おの の とうふう, Ono no Michikaze/Ono no Tōfū, 894 – 967), Fujiwara no Sukemasa (藤原佐理, ふじわら の すけまさ, 944 – 998) and Fujiwara no Yukinari (藤原行成, ふじわら の ゆきなり, 972 – 1027). All three were also outstanding calligraphers.

In 1001 C.E., Fujiwara no Yukinari wrote Haku Rakuten Shikan (白楽天詩巻, はく らくてん しかん), a compilation of poems (詩巻) by the Tang dynasty (唐朝, pinyin: Táng cháo, 618 – 907 C.E.) poet Bai Juyi (白居易, pinyin: Bái Jūyì, 772 – 846), whose courtesy name was Bai Letian (白樂天, pinyin: Bái Lètiān). Bai Juyi was an incredibly talented artist and started to compose his own poetry at the age of six.

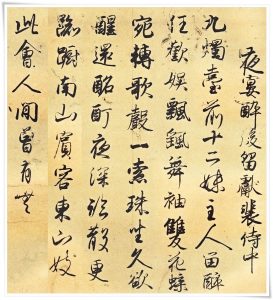

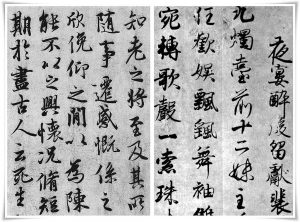

The Haku Rakuten Shikan (Figure 1) is written in a very warm yet refined style, displaying an elegant and sophisticated silhouette of wayou shodou in its full glory. Although a Japanese style, the technical foundations of wayou shodou are based upon the masterpieces of Wang Xizhi (王羲之, pinyin: Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361) of the Jin Dynasty (晉朝, pinyin: Jìn cháo, 265 – 420 C.E.). This is not surprising, particularly since the Tang dynasty put an end to the “elegance” of the style of the Jin period and introduced quite rigid calligraphy governed by strict rules. This tradition was revised during the Song Dynasty (宋朝, pinyin: Sòng cháo, 960 – 1279) by none other than the brilliant ink painter and calligrapher Mi Fu (米黻; pinyin: Mǐ Fú, 1051–1107), also known as Mi Fei (米芾, pinyin: Mǐ Fèi {trivia: 芾 can also be read “Fú”}).

Movie 1. Rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e. “copying {studying} masterpieces”) of a fragment of calligraphy titled Haku Rakuten Shikan (白楽天詩巻, はく らくてん しかん) by Fujiwara no Yukinari (藤原 行成, ふじわら の ゆきなり, 972 – 1027), Part I.

If you compare both fragments of calligraphy works shown in Figure 2., (left: The Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion” {蘭亭集序, pinyin: Lántíngjí Xù}, and right: Haku Rakuten Shikan), you can see that they resemble each other. Though if you look more closely and for an extended period of time, you will understand the subtle differences.

Movie 2. Rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e. “copying {studying} masterpieces”) of a fragment of calligraphy titled Haku Rakuten Shikan (白楽天詩巻, はく らくてん しかん) by Fujiwara no Yukinari (藤原行成, ふじわら の ゆきなり, 972 – 1027), Part II.

The calligraphy of Xizhi is written in a rather forceful manner with a more or less consistent thickness of line. By contrast, Yukinari uses ink accents similar to those in works written in Japanese kana script (かな), thus, one can immediately spot the places where the brush was refilled with ink. The contrast between thick and thin lines is more amplified, stimulating movement and enriching the flavour of this already dynamic style.

Movie 3. Rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e. “copying {studying} masterpieces”) of a fragment of calligraphy titled Haku Rakuten Shikan (白楽天詩巻, はく らくてん しかん) by Fujiwara no Yukinari (藤原行成, ふじわら の ゆきなり, 972 – 1027), Part III.

Studying Japanese calligraphy requires a solid foundation in Chinese shufa (書法, pinyin: shūfǎ, i.e. “calligraphy”). Without studying the origins of the latter, the concept of wayou shodou cannot be fully grasped. I prepared three videos in which I write rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e. “copying {studying} masterpieces”) of a fragment of Haku Rakuten Shikan (four poems of Bai Juyi written by Fujiwara no Yukinari). Although you can see only 25 minutes of me writing, it took me eight hours of research in order to comprehend and copy the detail of this masterpiece. That pictured is my second attempt at rinsho. I found it very soothing and relaxing to write, and the style truly magnificent. I ordered online a book depicting the whole compilation of poems written by Yukinari (including those of Bai Juyi), and I hope to study more works by this master. At the very end of Part III of the videos, you can see me signing my work with three characters: 龍涙臨 (りゅうるい りん, Ryūrui rin, i.e. “rinsho by Ryuurui”). This was only a fragment of the whole compilation, but if I were to write the entire text, I would be signing 龍涙全臨 (りゅうるい ぜんりん, Ryūrui zen rin, i.e. “rinsho of the whole {text} by Ryūrui”). I am certain that one day I shall.