1. Meaning:

correction; exam; printing; proof; school; archaic: assemble, join (wood).

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): あぜ, かせ, くらべる

- Onyomi (音読み): キョウ, コウ

- Japanese names: めん, ただす

- Chinese reading: jiào, xiào

3. Etymology

校 belongs to the 形声文字 (けいせいもじ, keiseimoji, i.e. phono-semantic compound characters). This is by far the largest group of Chinese characters, encompassing about 85 – 90% of all kanji which are constructed of semantic (disclosing the general nature of a character) and phonetic compounds (responsible for its sound, and often further narrowing the meaning of given character). Usually, semasio-phonetic characters have a semantically corresponding version in the form of another character of a more complex nature (so called 正字, せいじ, seiji, i.e. “correct” [traditional] characters). 校 is no exception. Please refer to Figure 5 to see one of its variants.

校 consists of two main radicals, which are 木 (き, ki, i.e. “wood”) and 交 (こう, kō, i.e. “mingle”, “mixing”). 木 is a pictograph of a tree, whereas 交 is the phonetic part of the character 校, and it has a slightly more perplexing etymology. It is quite often explained as timber planks or pieces of wood joined together. According to 說文解字 (Shūowén jiězì, i.e. “Explaining Simple [Characters] and Analyzing Compound Characters”) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by 許慎 (Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), 交 combined the meaning of a prisoner and a wooden device (used for imprisonment).

This theory is further confirmed in the Book of Changes, also known as Five Classics (易経, pinyin: Yì jīng) whose original text was written on bamboo slips around the mid-3rd century B.C. It is one of the oldest Chinese classics in existence. The book discusses 64 hexagrams, formed by six lines each, which form a divinatory system, similar to Western geomancy. In each hexagram there are two types of lines, unbroken and broken, that correspond to the elements Yang (陽, pinyin: Yáng, i.e. “sun” [the male element]) and Yin (陰, pinyin: Yīn, i.e. “shadow” [the female element]), respectively. Each of those lines has a separate commentary. For the purpose of explaining the etymology of the character 校, let us have a close look at the 21st hexagram. Its symbolic meaning is related to “gnawing bites” (噬嗑, pinyin: shì kè; which is further explained as various kinds of shackles used in imprisonment), and graphically it looks like this: ䷔ The first part of the commentary referring to the top unbroken line reads: 屨校滅趾 (pinyin: jù jiào miè zhǐ), which translates into “shackle sandals used for hurting (movement crippling) feet (toes)”, whereas the bottom one reads: 何校滅耳 (pinyin: hé jiào miè ěr), which could be understood as “neck shackles used for hurting an ear”.

The character 校 has multiple meanings, and there are multiple theories that explain it. For instance, in the word 学校 (がっこう, gakkō, i.e. “school”), the right hand-side radical 交 of the character 校 follows the shape of 爻 (こう, kō, i.e. “join”, “mix”), as in 敎, which is the traditional form of 教 (きょう, kyō, i.e. “teach”, “doctrine”). Consequently, in the word 校猟 (こうりょう, kōryō, “hunting game”), the meaning of the character 校 is to interrupt the hunted wild animal from getting away by “joining” (爻) or assembling timber or sticks to make a trap and catch it by that means. To read more on the character 学 (がく, gaku, i.e. “to study”), of which the traditional form is 學 whose top part compounds also correspond to the meaning of 爻, please read the article on its etymology, here.

In the word 校倉 (あぜくら, azekura, i.e. “ancient log storehouse”, the construction method that resembles the same one used for building a square shaped well entrance [timber logs assembled in a square formation]), 校 bears the same meaning (i.e. “arrange”, “assemble”)as in the above mentioned 校猟 (こうりょう, kōryō, “hunting game”). This further confirms the accuracy of this theory.

In words such as 校讐 (こうしゅう, kōshū) or 校書 (こうしょ, kōsho), both of them mean “to compare (比校, ひこう, hikō) certain words or phrases by the use of multiple books and their editions for cross reference purposes”, the character 校 means to “assemble” (books, etc., in order to compare against one another).

4. Selected historical forms of 校.

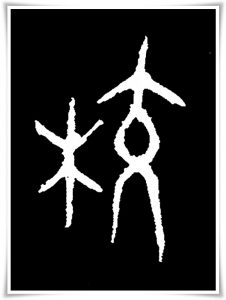

Figure 1. Oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) form of 校, from ca.1600 B.C., Shang dynasty (商朝, 1600 – 1046 B.C.).

Figure 2. Small seal script (小篆, しょうてん, shōten) form of the character 校 found in the 說文解字 (pinyin: Shūowén jiězì, i.e. “Explaining Simple [Characters] and Analyzing Compound Characters”) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, pinyin: Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.).

Figure 3. Ink rubbing of the clerical script form (隷書, れいしょ), or more precisely happun rei (八分隷, はっぷんれい, lit. “eight parts clerical [script]”) of the character 校, taken from the late Han dynasty (後漢, 25 – 220 C.E.) stele 韓仁銘 (pinyin: Hán Rén míng), dated 175 C.E.

Figure 4. A cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 校, from an ink rubbing from the work of Zhao Mengfu (趙孟頫, pinyin: Zhào Mèngfǔ, 1254 – 1322), Yuan dynasty (元朝, 1279 – 1368).

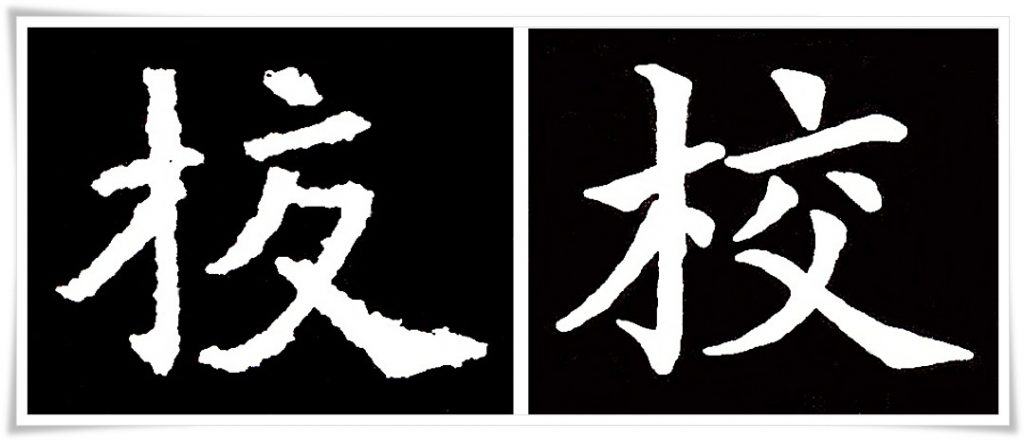

Figure 5. Ink rubbings of two variants (異体字, いたいじ, itaiji, i.e. “[Chinese] character variants”) standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) forms of the character 校. Left: from a magnificent 1300 characters long stele 蘇慈墓誌銘 (pinyin: Sū cí mù zhì míng), Sui dynasty (隋朝, 581 – 618), 603 C.E. Right: from the Tang dynasty calligraphy 五經文字 (pinyin: Wǔ Jīng wénzhì) in which proper forms of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) characters used in the Five Classics of Confucianism (五經) text were set forth.

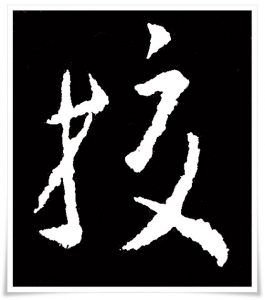

Figure 6. Ink rubbing of semi-cursive (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) from the character 校 found in the calligraphy work compilation entitled 集王聖教序 (pinyin: Jí Wáng shèng jiào xù), created on the order of the Emperor Taizong of Tang (唐太宗, pinyin: Táng Tàizōng), of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907). Characters for this work were chosen from masterpieces of Wang Xizhi (王羲之, pinyin: Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361), often referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖; pinyin: shū shèng), who lived during the Jin Dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420 C.E.).

5. Useful phrases

- 学校 (がっこう, gakkō) – school

- 高校 (こうこう, kōkō) – high school

- 校正 (こうせい, kōsei) – proofreading

- 校閲 (こうえつ, kōetsu) – revision, editing