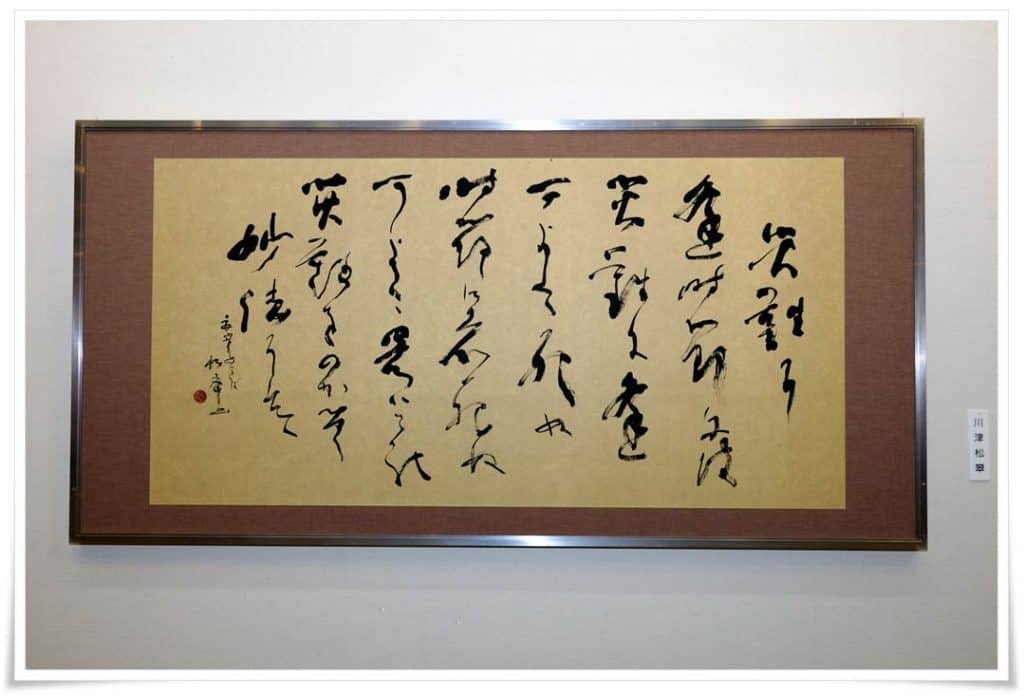

Figure 5 is a calligraphy of a poem by Ryōkan Taigu (良寛大愚, りょうかん たいぐ, 1758–1831), an eccentric Japanese Zen Buddhist monk and a hermit of the Edo period (江戸時代, 1603 – 1868).

災難(さいなん)に逢(あ)うがよく候(そろ)。

(sainan ni au jisetsu ni wa, sainan ni au ga yoku soro)

(shinu jisetsu ni wa, shinu ga yoku soro)

(kore wa kore sainan wo no ga ruru myōhō nite soro)

The text can be understood as follows:

This is a stunning work, written in Japanese 調和体 (ちょうわたい, chōwatai, i.e.”the harmony of scripts”). 調和体 incorporates the three writing systems of Japanese language: kanji (漢字, かんじ, i.e. “characters of Han China”), hiragana 平仮名 (ひらがな, i.e. “Japanese cursive syllabary”) and katakana (片仮名, かたかな, i.e. “angular Japanese syllabary”). The vivid and rhythmically complex cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) of this particular work perfectly emphasizes the unpredictable nature of our lives.

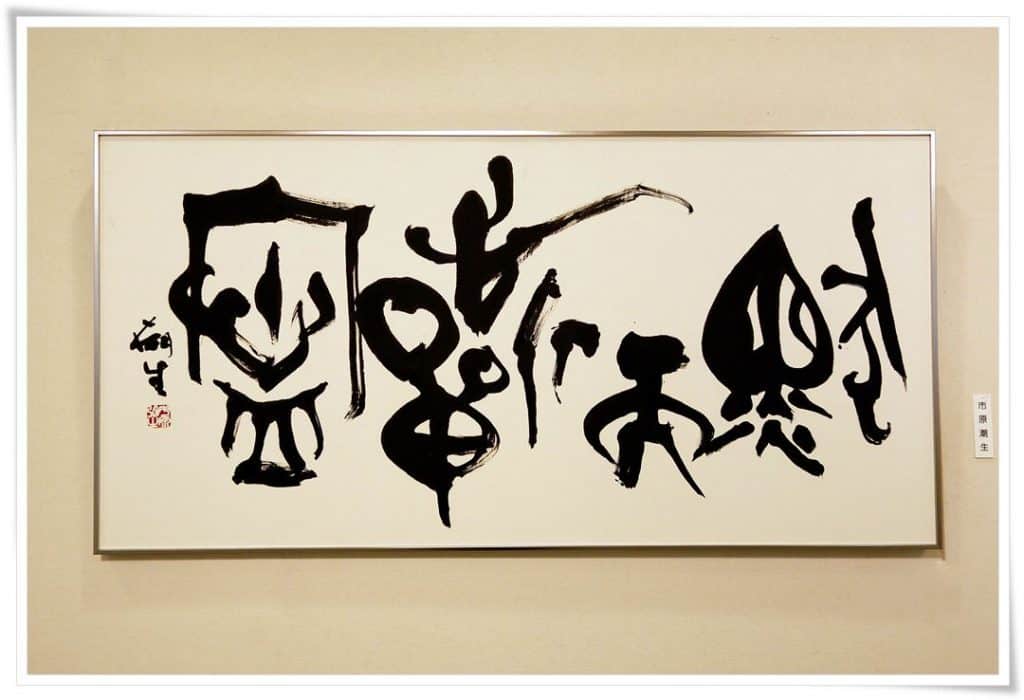

In Figure 6 you can see a very imaginative and stylized seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho) of the phrase 懐楽 (かいらく, kairaku). Depending on the meaning of the kanji (as one kanji may have many of them) we adopt, it could be translated as “wrapped in joy” or simply “happy heart (feelings)”. What a brilliant combination of the chosen style and brushwork, as well as the shapes of the characters, with this cheerful phrase.

The calligraphy in figure 7 is absolutely amazing. It’s a wild and “cursive” kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”). I wrote the word “cursive in quotation marks, as kinbun script, traditionally, does not have a cursive form. This is not only a very expressive work, but brilliantly arranged too. It seems that the line tells us many stories on its own, regardless of what the real meaning of this text may be. Simply by watching this calligraphy, would you ever guess that its meaning is religious and tranquil? The phrase goes 黙而祈寧 (Chinese: mò ér qí níng), which means “to become silent and pray peacefully”.

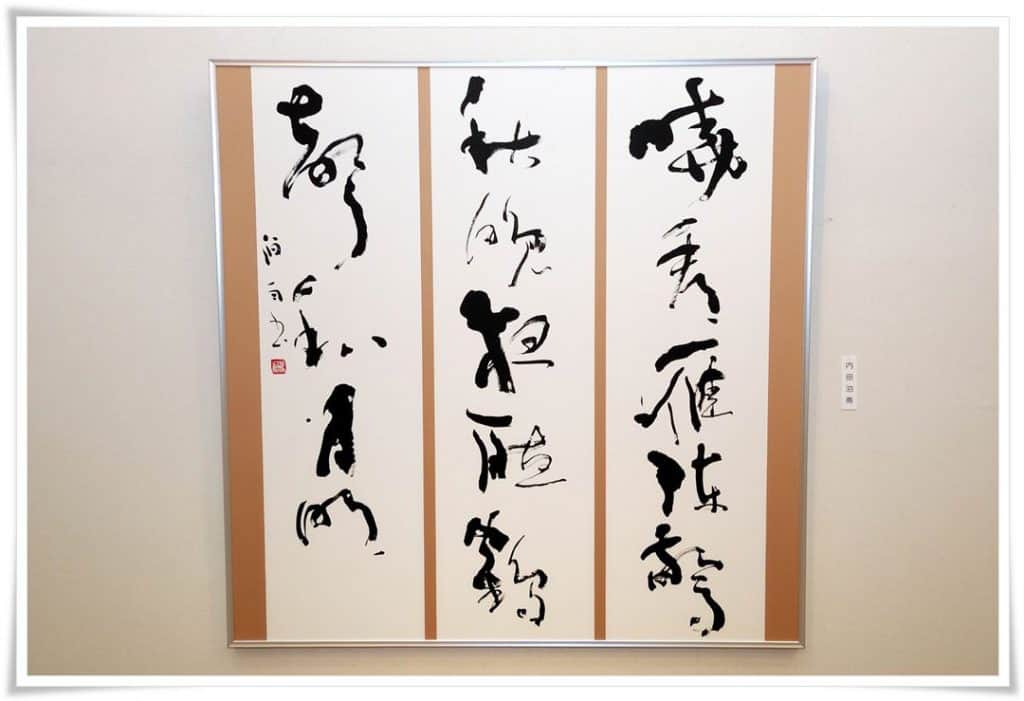

The last work I would like to talk about is the one shown in Figure 8. I chose it for the fantastic imagery of both its text and brushstrokes.

(Chinese: xiǎo kān yàn zhèn jīng qiū wǎn)

夜聽鶴聲和月明

(yè tīng hè shēng hé yuè míng)

Which I would translate as:

I watch the flange of wild geese taking off

And at night, I am listen to cranes’ calls

Harmonizing with the bright light of the moon

See the ink traces and imagine thousands of flapping wings. Sense the early morning fresh air in the dry strokes of the brush. Feel the movement of air in the thick vibrant vertical lines. Hear the calls of hundreds of birds in the evening air, resonating with the curved figures of the written characters. Turn your eyes to the moon lurking within the white glare of the paper sheet.

Calligraphy is like magic. It puts a spell on you, just like the bright moon.